If you're in charge of writing your nonprofit’s annual report, you're probably juggling at least three pressures at once: what the board wants to see, what funders expect to hear, and what your program staff are actually witnessing on the ground.

Those pressures show up most clearly in the language you choose for summary pages, pull quotes, and impact highlights.

I recently saw a callout quote in a report that said something like:

“Most people experiencing X don’t actually deal with Y.”

It was framed as a data point, but without any context, it raised more questions than anything.

Which program is this referring to?

Which year of data is this based on?

Does this consider all population or demographics groups served?

When I checked in with someone I trust working directly with this population, their lived experience didn’t line up.

That’s not necessarily because the data is wrong. It’s because it wasn’t explained.

This gap is where trust starts to slip.

The Real Challenge in How to Write an Annual Report

We tend to summarize too soon.

Community-centered work is complex: funding restrictions, program changes, shifting needs. But annual reports often try to compress all of that into one page—or worse, one headline.

This usually shows up in:

- the executive summary

- the “By the Numbers” spread

- the impact highlights page

- the opening letter from leadership

And that’s how we end up with swings like:

“The need has never been greater” (based on intake numbers)

“Outcomes are improving” (based on follow-up surveys)

Both might be true, but not for the same group of people.

→ Click here to get the free Belief-Building Annual Report Playbook

%20(1).png)

Get The Belief-Building Annual Report Playbook

The Belief-Building Annual Report Playbook

Enter your info and we’ll send the postcards straight to your inbox:

Donor Thank You Postcards Templates

Enter your info and we’ll send the postcards straight to your inbox:

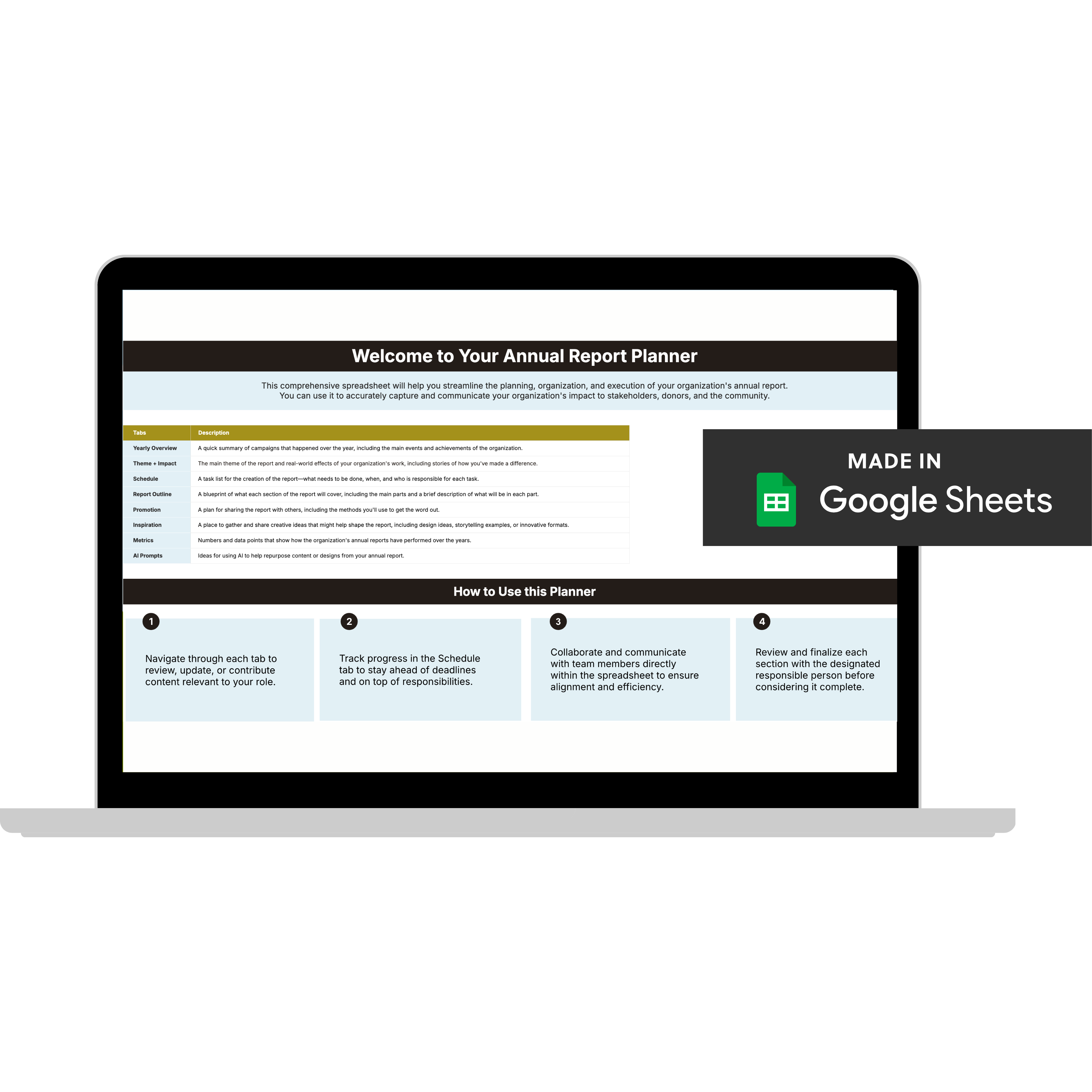

Annual Report Planner

Get a clear content roadmap so your annual report builds belief, earns trust, and actually gets used after launch—plus the same planning approach we use with our 1:1 clients, built in.

Annual Report Planner

Get a clear content roadmap so your annual report builds belief, earns trust, and actually gets used after launch—plus the same planning approach we use with our 1:1 clients, built in.

Why “Most People” Is a Red Flag in Annual Reports

Phrases like:

- “Most people experience…”

- “The majority of families don’t…”

- “Typically, clients no longer face…”

Sound confident, but leave gaps. Readers start wondering:

- Who’s counted in that “most”?

- Were they long-term participants or crisis intakes?

- What about the folks who dropped out early?

When that info is missing, it doesn’t just feel incomplete. It feels curated. And people feel that, even if they can’t name it.

How to Write an Annual Report With Specificity (Without Undermining Confidence)

Here’s how to build trust without oversimplifying:

1. Be precise about who you’re talking about

Replace generalities such as “people,” “families,” or “clients” with specific groups.

Instead of:

“Most people experiencing food insecurity…”

Use:

“Among households enrolled in our weekly grocery distribution for at least six consecutive months…”

Specificity builds trust.

2. State what the data includes AND what it excludes

Your charts don’t need to tell the full story, but they should say which slice they’re showing.

Try adding:

“Based on participants who completed a 90-day follow-up survey.”

“Emergency intakes not included.”

That one line protects the integrity of your work.

3. Connect stats to real-world outcomes

Numbers feel abstract unless they’re grounded in reality.

Instead of:

“62% reported improved food stability…”

Follow with:

“For one parent, that meant no longer skipping meals at the end of the week to feed their kids.”

It helps the reader feel the data.

4. Name variation instead of smoothing it out

Progress rarely looks the same across programs. Say so.

“Outcomes differed between urban and rural sites.”

“Retention was stronger among families with stable housing.”

This doesn’t weaken your case, it strengthens credibility.

Your annual report is a tool for belief.

Annual reports are not skim-only documents.

They are reviewed by:

- board members assessing strategy

- funders figuring out if they should continue to invest

- partners considering alignment

- staff looking for reflection of their work

These readers are capable of nuance.

They expect accuracy more than optimism.

If your goal is belief—belief in the mission, the model, and the people doing the work—the answer isn’t cleaner stories.

It’s more context.

People don’t lose trust because the work is complex.

They lose trust when complexity is hidden.

That’s the real work of writing an annual report that engages supporters and builds belief.

If you’re reworking how to write your annual report this year and want tools that support specificity—not surface-level polish—you may want to start with The Belief-Building Annual Report Playbook.